Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

English-language books originally written in Japanese

Introduction

As of 2003, fifty-eight years have passed since Hiroshima and Nagasaki suffered the devastation of the A-bombing. While there is concern about the loss of eyewitnesses with the death of aged hibakusha, (A-bomb sufferers), people are making unceasing efforts to succeed in passing on the legacy of their experiences to the world through the publication of A-bomb literature in English.

The purpose of this part is to introduce English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki originally written by Japanese authors. By recording the total number of such books published each year since 1945, this part attempts to demonstrate the process of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s globalization through the publishing of English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s experiences. It also discusses what has yet to be done: the distribution of copies of books in English to grass-roots organizations, and the multi-lingual publication of A-bomb literature.

In Part 1, a total of 446 English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki written by Japanese and non-Japanese authors were introduced. Of these, 283 are English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki originally written by Japanese authors.

l. Toward the global inheritance of the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Hibakusha and citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have endeavored to spread their experiences to the world in the following ways:

1) A-bomb survivors have testified about their experiences abroad.

2) Signature collection campaigns have been conducted.

3) Resolutions adopted in meetings and conferences held in Japan are sent to political leaders abroad and to the United Nations.

4) Exhibitions of A-bomb materials are held abroad.

5) A-bomb literature has been translated into foreign languages. A-bomb survivors have been the driving force for the publication of their accounts in English.

This part, focusing on the last activity, discusses the role played by A-bomb literature available in English during the last fifty-eight years. In order to demonstrate year-by-year publication trends, the author has classified the last fifty-eight years into six periods of approximately ten years each, as shown in Table 1.

Periods Years Covered Characterized by

1 1945-1954 US occupation of Japan

2 1955-1964 Japanese movement against A- and H-bombs

3 1965-1974 Following the split of the movements against A- and H-bombs

4 1975-1984 International sharing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki experiences

5 1985-1994 Development of international solidarity with those exposed to radiation

6 1995-2002 Following the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Table 1: Classification of A-bomb and H-bomb Literature by Publication Date

The famous peace activist, Barbara Reynoldsl) insisted on the necessity of more English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in her essay in the fall issue of Nagasaki no Shogen (Witness of Nagasaki), 1980. She also claimed in the article that for 350 Japanese-language books translated from English, there was only one English-language book translated from Japanese, and that the publication was a novel. In fact, at that time there were still relatively few English books originally written in Japanese; only 72, comprised of 5 literary works, 2 pieces of juvenile literature, 23 memoirs, 13 photographic records, and 29 reports. When we compare the number of publications as of 1980 according to genre, researches and reports were the most widely published, followed by memoirs.

However, in one important respect, Reynolds’ comment is accurate. We can classify the books according to whether they have distribution channels to retail bookstores (that is, publications by commercial publishers) or whether they do not (such as private publications by individuals, groups, associations, and by public organizations such as schools and cities). As of 1980, 65% of the literary books, including juvenile literature, were published by publishers with distribution routes to retail bookstores. On the other hand, 80.5% of the memoirs belong to the other category2). Similarly, only 15.2% of research and reports were published commercially, while the rest were published privately or by public organizations such as schools or municipal authorities. As a result, literary works and juvenile literature in English with comparatively large circulation were more readily available at bookstores than publications in other genres. The percentage of publications by publishers has not changed much to this day. One important aim of Part 1 is to introduce the books that cannot easily be found at bookstores.

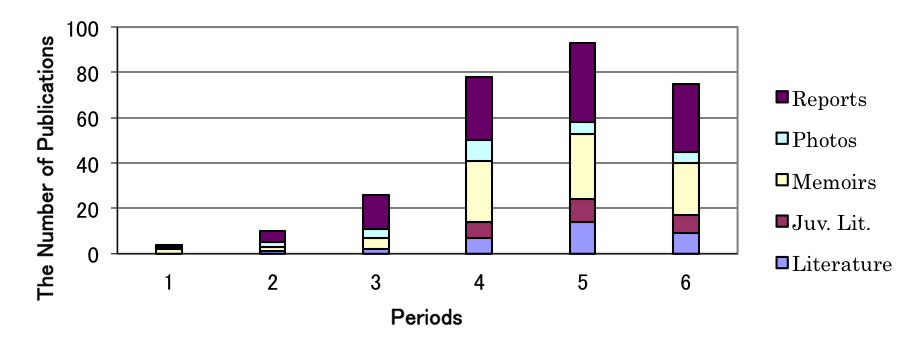

Twenty-three years have passed since Reynolds’ plea in 1980. How many books have we added to the category of A-bomb literature? As of May 10, 2003, 283 English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, originally written by Japanese authors, have been confirmed. As described above, they are categorized into six periods according to their date of publication. Figure 1 shows that the number of such publications has increased steadily. Especially in the fourth period, the number of English-language memoirs rose sharply. Following the 40th anniversary of the A-bombings in 1985, the number of publication has not fallen at all; rather, it increased still further in the fifth period. In this period, the numbers of English-language literary works and research and reports doubled from the previous period (from 8 to 15, and from 23 to 35 respectively). Memoirs also increased steadily. Surprisingly, publication has been going on even after the 50th anniversary3). These figures confirm that the role of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has not diminished but is as relevant as ever.

Figure 1: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English from 1945 to 2002

This yearly increase of the number of publication shows the process of passing the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the world. What has driven the Japanese to translate and publish A-bomb literature in English? In the following chapter, the process of globalization of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the role played by English-language A-bomb literature are discussed for each period.

The Process of Globalization of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

l. The First Period (1945-1954)

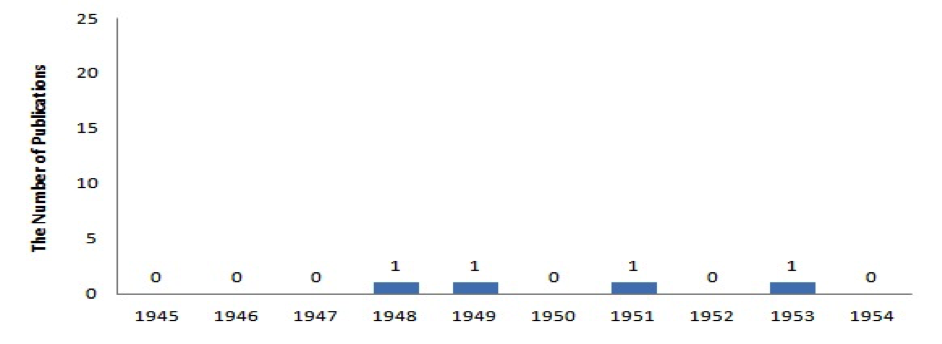

Figure 2: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English during the first period

In the first period, non-Japanese played the major role in letting the world know about the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki4). The Japanese, especially A-bomb survivors, were in too much hardship surviving the hard postwar living conditions and struggling against the aftereffects of A-bomb disease to think of writing their accounts of these experiences, still less of publishing them in English5). There are only four English books originally written by Japanese authors during this period. The first is Living Hiroshima: Scenes of A-bomb Explosion with 378 Photographs Including Scenery of Inland Sea (1948) edited by Kenzo Nakajima. This book contains photographs which show the reconstruction of the city and survivors’ stories, including those of the six witnesses recorded in John Hersey’s Hiroshima. Another is Yuko Matsumoto’s My Mother Died in Hiroshima (1949)6). This English booklet was originally published in 1949, and later reprinted in Japanese and English editions by the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation. The third is Takashi Nagai’s We of Nagasaki: The Story of Survivors in an Atomic Wasteland (1951). A doctor in Nagasaki, Nagai lived in a one-room cabin with his son and daughter after his wife’s death in the bomb blast. He also suffered from A-bomb disease following his relief work as a doctor and died, leaving his children orphaned. He collected the accounts of eight survivors including those of his son and daughter. The English and German editions of this work provoked a public response abroad.

The fourth book published during this period is a medical report, Atomic Bomb Injuries, written by Nobuo Kusano. The first edition, published in 1953, was republished in 1995 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the A-bombing. Kusano was an assistant researcher at the Institute of Infectious Diseases at Tokyo University. At the request of the Sanitation Department of Hiroshima Prefecture, which claimed that patients exhibiting dysentery-like symptoms were dying one after another, he entered Hiroshima at the end of August, 1945, and helped perform autopsies of the victims7). He first reported the reality of the atomic bomb disaster at the International Doctors Conference held in Vienna in 1953. He and other Hiroshima doctors, who have conducted research on A-bomb diseases and treated A-bomb survivors for over half a century, are required to make available the knowledge they have amassed.

In the following year, 1951, when the U.S.-Japan Peace Treaty was signed, the August 6th issue of The Asahi Graph, a major news magazine in Japan, featured the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. For many Japanese people, this was the first time for them to be informed of the facts about what had happened in the two cities. The Korean War had already started, and the U.S., Britain, and the USSR were conducting nuclear tests. University students and labor union members held peace rallies to protest against A- and H-bomb tests8), but it was not until the second period that ordinary Japanese people took part in the mass movements.

2. The Second Period (1955-1964)

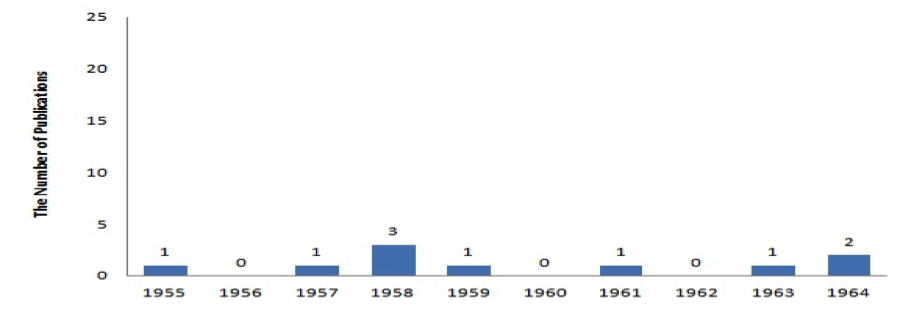

Figure 3: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English during the second period

The direct origin of the mass movement of the second period can be traced to when a tuna fishing boat called the Lucky Dragon No.5 was showered with radioactive fallout from a U.S. H-bomb test on Bikini Atoll, resulting in human deaths9). As a consequence of this upsurge, the First World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima from August 6 to 8, 1955. In the Hiroshima Appeal issued by the delegates, international solidarity was one of the main goals10). This occasion caused hibakusha and other citizens to turn their eyes to the world for the first time. To fulfill the main purpose, the resolution promoting international cooperation, they started sending delegations including hibahusha and doctors to Europe and to Asian countries such as India, Ceylon and Indonesia. Dr. Yoichi Fukushima reported after this overseas speaking tour that it was crucial to inform the world of the aftereffects of A-bomb disease11). Physical and Medical Effects of the Atomic Bomb in Hiroshima (1958) is the first comprehensive report available in English, with 117 pages by a Japanese researchers’ group composed of physicists, chemists and medical specialists. This book consists of three parts: physical and statistical investigations, pathological investigations, and clinical investigations of chronic injuries caused by the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. The researchers claimed that there had not been a comprehensive report concerning A-bomb diseases from various fields of study.

In spite of the movement against A- and H-bombs and subsequent dispatch of A-bomb survivors abroad, there were few publications available concerning the real facts of the damage caused by the bombings. In this period, however, two Japanese language memoirs were translated into English. Both have gone through several editions and been widely read among non-Japanese. One is Michihiko Hachiya’s Hiroshima Diary (1955). The author, the then director of Hiroshima Communications Hospital, kept a detailed diary of what he saw and did at the time of the bombing and during its aftermath. The other is Arata Osada’s Children of the A-bomb (1959). An Emeritus Professor of Education and former president of Hiroshima University, Professor Osada collected 105 accounts of the bombing provided by the children of Hiroshima. The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, established after the first World Conference in 1955, split in 1963 because of a conflict of opinions concerning the Soviet Union’s nuclear testing and the partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Thus the nationwide anti-nuclear movement that had originated at a grass-roots level and involved a wide range of ordinary Japanese people, was left in confusion.

3. The Third Period (1965-1974)

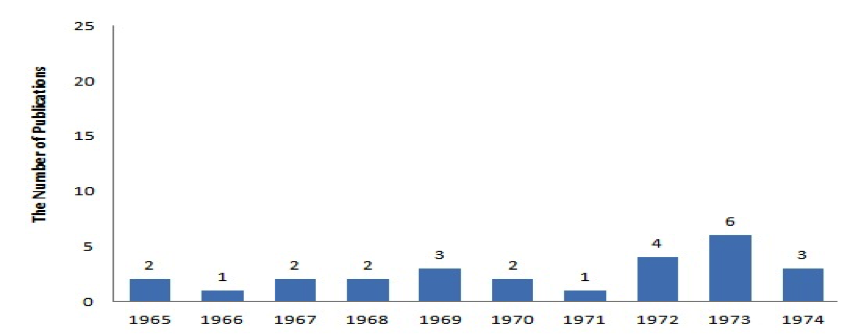

Figure 4: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English during the third period

In 1963 the Japan Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions of Japan withdrew from the World Conference and the Japan Council against A-and H-bombs, and formed an interim group which later became the Japan Congress against A- and H-bombs. Nationwide peace movements, which had arisen spontaneously among the people, were thrown into confusion. Some gave up their activities with a deep distrust of political parties’ direction of anti-nuclear movements. Others embraced the activities led by hibakusha such as appealing to the government to enact a hibakusha relief law12) and to compile a comprehensive report on the damage caused by the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

During this third period, characterized by a postwar politics-ridden nuclear movement in Japan, some researchers tried to reaffirm the historical significance of “Hiroshima and Nagasaki” and scientifically classify data concerning the damage done to the two cities. It was in this context that a report on damage caused by the atomic bombings was published: Actual Facts of the A-bomb Disaster (1964), originally written in English for the members of the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Mission to bring abroad with them. This tour plan originated with Barbara Reynolds. The mission, with 40 members including hibakusha, peace activists and medical personnel, set out for a 75-day tour in Europe and the United States13).

The publication of research and reports more than doubled during this period (from five in the second period to twelve). In 1969, an English-language book was published on the postwar history of Hiroshima, Hiroshima: Steps Toward Peace. This may be the first book, compiled by the Hiroshima-residing researchers, to focus on relief activities for survivors, cultural and social activities by citizens, and three antinuclear groups’ movements. Barbara Reynolds was one of the translators of this book.

Medical reports written by doctors also increased during this period. Among them is an outstanding publication: Copies of Translated Japanese Reports Regarding Medical Effects of the Atomic Bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1965, 465 p.). The investigations concerning effects of the A-bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki undertaken by Japanese physicians and scientists from August through December, 1945, were declassified by the U.S. government twenty years after the bombings.

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary, Hiroshima Prefecture issued a pamphlet, titled 25th Anniversary of A-bomb Day August, 1970, to describe the actual conditions of the damage of the A-bomb and the state of affairs concerning the care of sufferers 25 years later.

The international situation was tense because of the Vietnam War. However, there were still insufficient numbers of English-language publications to convey the atrocity of nuclear war. In the next period, the globalization of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made great strides.

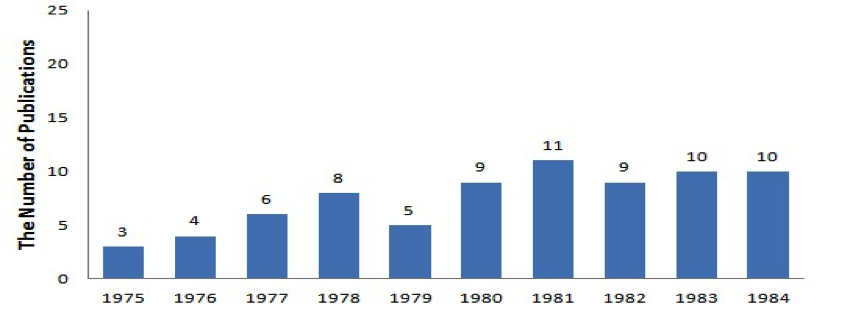

4. The Fourth Period (1975-1984)

Figure 5: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English during the fourth period

The International Symposium on the Damage and Aftereffects of the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was held in Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki from July 2l to August 9, 1977. The declaration of the symposium, "We are all survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. We also are hibakusha, as the survivors of those cities call themselves”14), symbolizes the new stage of anti-nuclear movements. In all, 69 specialists from 22 countries attended this symposium. The report based on the results of the survey of the A-bomb survivors’ actual conditions was adopted and submitted to the United Nations. This occasion played an important role in spreading the facts of A-bombs to the world15).

In the second period, a slogan, “the only country to have been subjected to nuclear bombings”, bonded Japanese people’s opinions together16). However, the declaration of the symposium shows that in the late 1970s it was time, for the survival of humankind, for the rest of the world to share the experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The report of the NGO symposium, A Call from Hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1978) contains papers from various fields, such as physics, medicine, sociology, and peace education. Prior to this symposium, Nagasaki city published Report on the Damage and After-effects of the Atomic Bombing in Nagasaki, 1945.

Furthermore, the NGO symposium prompted a citizens’ movement to publish a photographic record with English captions, Hiroshima-Nagasaki (1978). According to the publication committee’s explanation on the birth of the idea, the plan for the book originated from “what was almost a casual idea”l7). A couple in Saitama Prefecture took their children to Hiroshima, and thought of creating an account of the bombings. A committee was formed in 1977 and held a small photo exhibition along with the NGO symposium. This movement is one of the typical examples that publication of an account in English is the main purpose of a volunteer citizens’ peace movement. Thousands of volunteers and hundreds of organizations, including international sponsors and co-sponsors, cooperated to publish this 340-page pictorial record. They planned, edited, published the book, and distributed the copies under their own power. In a booklet about the publication committee, Days to Remember (1981), they say that in the three years following the publication, over 15,000 volumes were sent abroad, and they received 200 letters of support. They presented a copy of the book to each representative attending the United Nations Special Session for Disarmament, and to each member of the Senate of the United States. They also displayed 150 photo-panels in Dag Hamarskjöld Plaza in the United Nations building, New York. The photo exhibitions have been held in more than ten countries including the Soviet Union, France, Bulgaria, Sweden, Finland, Poland, East and West Germany, Denmark and North and South American countries. They report that over one hundred thousand people have seen the panels18).

Thus the meaning of survival in the two cities was broadened in the fourth period, which coincided with Europeans’ concerns about a possible “Euroshima”. During this period, when it was feared that Europe might be the stage for a limited nuclear war because of the Cold War, hibakusha’s eyes were turned abroad further: they were among 500 delegates to a 1978 Special Session of the United Nations General Assembly on Disarmament, held in New York City. Their attendance was supported by a petition with more than 18 million signatures for the abolition of nuclear weapons throughout the world. A report to explain the hibabushas’ requests and the actual conditions of A-bomb damage in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, To the united Nations 1976, had been published prior to their trip. The delegates submitted it to the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

On the 30th anniversary of the A-bombings in 1975 a compilation of materials on damage caused by the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was published in Japanese. This is a comprehensive report written by thirty-four Japanese specialists in the fields of physics, medicine, social sciences, and humanities, which had been a long-outstanding issue since the end of the war. The 706-page English edition, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings (1981), was published six years later. This book consisted of four parts: physical aspects of destruction, injury to the human body, the impact on society and daily life, and moves toward the abolition of nuclear arms. As such, it presented an ordered record of all available scientific findings on atomic bomb damage. The Impact of the A-bomb: Hiroshima and Nagasaki 1945-1985 (1985), which adds some new material on the A-bombings and their aftermaths, is an abbreviated version for the general reader.

uring this fourth period, Hiroshima and Nagasaki doctors were dispatched to investigate the residents near the nuclear testing site on the Marshall Islands and to Korea to examine the Korean sufferers of the A-bombs. It was not until 1964 that the Japanese people started to recognize hibakusha living abroad19). In that year, the A-bomb Survivors’ League was established in Okinawa, which was still under U.S. sovereignty. The hibakusha living in Okinawa requested that doctors be sent to them. The delegations to investigate hibakusha in Korea reported after their visit on the existence of 5, 000 hibakusha there20). Thomas Noguchi, a Japanese American leader of the hibakusha relief movement in the United States, visited Hiroshima and mentioned the actual situation of A-bombed Japanese Americans. It was not until ten years later in the 1980s, that researchers realized that there were also hibahusha in South America. Yoshiro Egami researched on the situation of the foreign students from South East Asia in the aftermath of the atomic bombing based on the author’s interviews with forty-three people (Egami, Yoshiro/ “Foreign Students from South East Asia and the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima”/ Regional Studies (Vol. 20, No. 2)/ Kagoshima/ Kagoshima Keizai University, 1993). To date, there have been no comprehensive English-language books about hibakusha living abroad21).

For Korean A-bomb survivors, two books were published to report the present situation of Korean survivors: The Atomic Bomb Survivors in Korea (1978) and The Other Hiroshima: Korean Atomic Bomb Victims Tell Their Story (1982). The former book was compiled by the National Council for Peace and against Nuclear Weapons. The author of the latter book tracked down Korean A-bomb victims and recorded the stories of eight of them. These books explain why there had been so many Korean hibakusha in Korea as well as in Japan.

During the fourth period, the number of English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki originally written by Japanese authors increased sharply (from 23 books in the previous period to 75 books). Moreover, the number increased every year. The increase of memoirs is outstanding (from six books in the previous period to 26 books). The number of publications telling how the A-bomb survivors still suffer from aftereffects also rapidly increased during the fourth period, but it was in the fifth period that A-bomb survivors would seek solidarity with those exposed to radiation abroad.

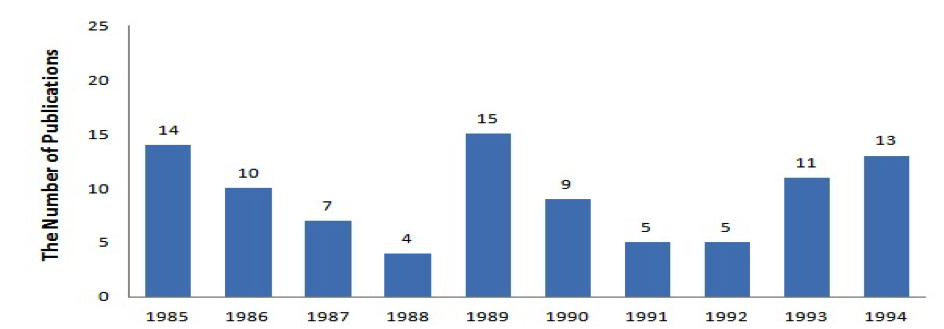

5. The Fifth Period (1985-1994)

Figure 6: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English during the fifth period

The shift from the role played by Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan to their role in the world has become more evident since the late 1980s. Requests for Hiroshima and Nagasaki doctors, for instance, became more critical than ever when there was the Chernobyl nuclear reactor core meltdown in Ukraine in 1986. Ten years after the accident, a medical report was published by Hiroshima doctors: The Chernobyl Accident: Thyroid Abnormalities in Children, Congenital Abnormalities and Other Radiation Related Information-The First Ten Years/ 1996. In the Preface,

Nobuo Takeichi mentions that he embarked on the publication projected because the local doctors who had been engaged in treating the Chernobyl victims following the accident often requested information on radiation injury in book form. Yukio Satow, in his essay, “General Review of the Late Effects of the Chernobyl Accident: Comparison between Chernobyl and Hiroshima”, contained in this book, says that in his twelve visits to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) all said that the tragedy of Chernobyl is a tragedy of all humankind, not just the CIS, and that that is exactly what Hiroshima has preached to the world about its tragedy. He concludes that an international joining of hands to spare future generations the same suffering will reduce the agony of today's victims.

To meet increasing demands for Hiroshima doctors, Hiroshima International Council for Health care of the Radiation-Exposed (HICARE) was established in 1991. HICARE's main activities were dispatching and accepting of doctors to and from foreign countries for training, conducting surveys and research on A-bomb sufferers’ health, and organizing symposiums. The report, originally written in Japanese, was translated into English and Russian. The English version is Effects of A-Bomb Radiation on the Human Body/ 1995, 419 p. An abbreviated version is A-Bomb Radiation Effects Digest / 37 p.

By this time, the meaning of the word hibakusha had broadened to include all those who are exposed to radiation. Those who had worked against A- and H-bombs sought for solidarity with all those who were exposed to radiation, including people living near nuclear testing sites, workers at uranium mines, and victims of nuclear reactor accidents. The media started to use katakana characters, the term ヒバクシャ22), to refer not only to the radiation victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also to those who were exposed to radiation as a result of nuclear tests and accidents at nuclear power stations. A report on cases of radioactive contamination from all over the world, The Exposure, was written by a team of journalists from the Hiroshima-based Chugoku Newspaper.

This increasing solidarity has also activated doctors’ exchanges of information about the treatment of the exposed to radiation. In Nagasaki, three symposiums were held in 1993 and 1994. Nagasaki Symposium on Chernobyl: Update and Future (1994) is the published proceedings of the symposiums. The aim of the symposiums was to provide Russian doctors with training sessions using the achievements of research and treatment of A-bomb survivors.

In 1995 Hiroshima and Nagasaki held the 50th anniversary of the bombings with this new understanding of hibakusha. Peace activists, A-bomb survivors, and authors whose subjects were Hiroshima and Nagasaki began to put in serious efforts to publish their books on this special occasion.

The number of publications in the year of 50th anniversary of the A-bombings and after (details of which are newly added for this revised version), is a reflection of the voices of hibakusha and other related people calling out that Hiroshima and Nagasaki still have roles to play.

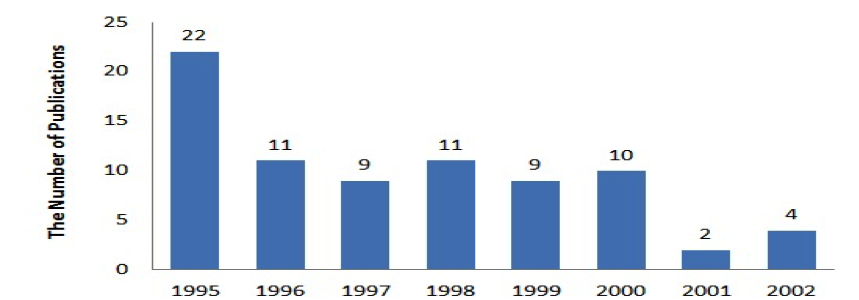

6. The Sixth Period (1995-2002)

Figure 7: Japanese A-bomb literature translated into English during the sixth period

The year of the 50th anniversary of the bombings saw the greatest number of English-language books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in Japan as well as abroad, in the history of A-bomb literature publication23). For the English-language publications in and after 1995 by Japanese authors, there are four main features:

l) In the year of the 50th anniversary, books which have become what is called classics of A-bomb literature written by well-known novelists were reprinted with a large circulation by major publishers. These include Makoto Oda's H: A Hiroshima Novel, and Kenzaburo Oe's Hiroshima Notes. Michihiko Hachiya's Hiroshima Diary, which is a record of the doctor’s account in the form of a diary, and Toyofumi Ogura’s Letters from the End of the world: A Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima, which is an account written in the form of letters to the author's dead wife. These have helped lay-people gain firsthand access to A-bomb literature.

2) It has become generally accepted that graphic and photographic records should have bilingual (Japanese and English) captions. In many cases, people who go abroad take copies of such books with them to show the damage caused by the A-bombings. Records of the Nagasaki Atomic Bombing, containing the exhibition in Nagasaki A-bomb Museum, was planned in the year of the 50th anniversary and published in the following year. The Spirit of Hiroshima: An Introduction to the Atomic Bomb Tragedy (1999) is the first official photographic record with Japanese and English captions showing the exhibition in the Hiroshima Peace Museum.

3) Publications by doctors stand out. The accumulation of collected data and medical treatment conducted in Hiroshima and Nagasaki for more than fifty years enabled doctors to identify a current problem in the world: radiation contamination. Many reports were published in 1995 about doctors’ activities, such as relief activities after the A-bombings, treatment of aftereffects for more than 50 years, and training doctors who treat those who were exposed to radiation. Doctors’ Testimonies of “Hiroshima”: A Report of the Medical Investigation into the Victims of the Atomic Bombing (1995), edited and published by Kyoto Physicians’ Association Appealing the Prevention of Nuclear War and the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons, retraces field surveys in Hiroshima started in August 9, 1945. Nagasaki Symposium Radiation and Human Health: Proposal from Nagasaki (1996) is the proceedings of the Nagasaki symposium hosted by the Nagasaki Medical Association for Hibakusha’s Medical care. Effects of A-Bomb Radiation on the Human Body (1995) is edited by HICARE.: Effects of Low’ Level Radiation for Residents near Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site: Proceedings of the Second Hiroshima International Symposium, Hiroshima, July 23-25 (1996) reports the international symposium held in cooperation of Japanese and Kazak doctors. Kenjiro Yokoro, Emeritus Professor, Hiroshima University (pathology), says in his essay, “Atomic Bomb and IPPNW” in Atomic Bomb Injuries (1995), that in spite of great leaps in medicine and biology, the ultimate treatment of radiation disorders has not been discovered, therefore, prevention of nuclear war is the only means of achieving this. This comment typifies Hiroshima and Nagasaki doctors’ opinions.

4) Aged hibakusha endeavor to leave their accounts while they are still alive (The Dome in August / 1997; Living through the 20th Century/ 2000). The survivors appeal to the world that humankind should never commit the same misdeed (Testimonies from Hiroshima, Nagasaki/ 1995; Hand them down to the Next generations! / 1995; Peace Ribbon Hiroshima; The witness of A-bomb Survivors; Toward Tomorrow/ 1997). Also, they believe that those who have survived the first atomic holocaust have a responsibility to work for the abolition of nuclear weapons (The Song of Tokoroten/ 1998; Pica-don/ 1995; Testimonies from Hiroshima, Nagasaki/ 1995: Hiroshima Witness for Peace: Testimony of A-bomb survivor Suzuko Numata/ 1998). Moreover, they are determined to appeal to the world as long as nuclear weapons remain a threat to the planet (Footsteps of Nagasaki: Excerpt from “Anohi Anotohi” / 1997; Burnt Yet Undaunted / 2002). In many cases, voluntary translators have shared their desires and have worked with the survivors.

There are several examples of attempts at multilingual publications. Although it is well-known that John Hersey’s Hiroshima and Eleanor Coerr’s Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes have been translated into many languages, there are not many books published by volunteers as a form of peace activities. However, the picture book for children, PIKA: Kei & Takkun’s Nuclear Trip (1987), is one example. The original Japanese book was translated into thirteen languages. The author published the English, Russian, French and Chinese versions for children in the countries which possess nuclear arms; the Hindi, Sinhalese, Thai, and Swahili versions for Asian and African children, the Esperanto version for people all over the world; the Polish version for those whose chances to know about A-bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are limited. In addition, there are Spanish and German versions. Another example is a collection of hibahusha’s accounts, The Unforgettable Day (1992). The original Japanese book was translated into four languages: English, Russian, Esperanto, and Lithuanian. Each edition has a circulation of one thousand and the English edition has been reprinted twice.

Moreover, there are some books which contain texts in more than two languages. A volunteer group in Nagasaki edited and published a multilingual (Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean) guidebook of Nagasaki, Nagasaki peace Trail: mutual understanding from peace Nagasaki. Nagasaki is located on Kyushu, the southern-most island of the Japanese archipelago, and has many Asian visitors every year. The preface says that the aim of the multilingual publication is to nurture the friendship with neighboring countries. Another example is the script of a documentary film on Korean A-bomb survivors, To the People of the World (1994). This book contains the script written in eight languages: Korean, Chinese, English, German, French, Spanish, Russian, and Japanese. The aim of this multilingual publication is to make known to the world the Korean A-bomb survivors’ requests to the Japanese government for compensation, and the abolition of racial discrimination against Koreans living in Japan.

Those who are concerned with the task of multilingual publication share a common motive: to spread their appeals to more people on the earth beyond English-speaking people. Among the languages used in the world, the number of Chinese-speaking people ranks first (1025 million), followed by English (497 million), Hindi (476 million), and Spanish (409 million) 24). Compared with the volumes of English books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the publication of books available in other languages is still rare. We will have to wait until a future generation achieves this.

Conclusion

How much have we managed to achieve of what Barbara Reynolds hoped for in 1980? Figure 1 shows how people have made strenuous efforts to make known the Hiroshima and Nagasaki stories to the world and have never abandoned their attempt, even after the year of the 50th anniversary. This is also an indication of the process of globalization of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We have two years left until we commemorate the 60th anniversary to be held in 2005. How many books will we be able to add to the total in the year? The total number of publication during the sixth period may match that of the fifth period, or even exceed it.

What remains to be achieved is to find ways to distribute the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to the masses of people abroad. It is sometimes said that the copies of some books are piled up in the authors’ houses or the publishers’ offices without any ideas about how to distribute them. The volunteer movement involved in publishing the photographic record, Hiroshima-Nagasaki, and sending gift copies abroad might show us a way to solve this problem. It is hoped that a movement to send copies of A-bomb literature abroad may take place in the future. Members of the Association for Peace Exchange with Indian & Pakistani Youth, a voluntary group in Hiroshima led by Haruko Moritaki, took copies of books on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to India and Pakistan in February, 2000, to donate them to schools and institutions. After returning to Japan, they reported that graphic resources with description of facts with survivors’ stories attracted the attention of a wide range of people. English editions have played a certain role among educated people for a long time; however, the future problem for us to solve is how the learning of Hiroshima and Nagasaki can infiltrate into the grass roots worldwide. To attain this goal, multilingual publication of A-bomb literature is what we wish the next generation to pursue.

Notes:

- Barbara Reynolds was an honorary citizen of Hiroshima and founder of the World Friendship Center in Hiroshima. As an American Quaker and pacifist, she dedicated her life to service to the survivors of Hiroshima. For further information, refer to the following books: Reynolds, Barbara/ Good-bye to Hiroshima/ 1969. Reynolds, Jessica/ To Russia: with Love/ 1962. The book is Barbara Reynolds' logbook of her voyage in a yacht to Nakhotoka to protest against the Soviet resumption of nuclear testing in 1961. The author, Jessica Reynolds, is Mr. & Mrs. Reynolds’ daughter. They entered the U.S. nuclear testing area in the Pacific as a protest in 1954. Linner (1995) writes about Barbara Reynolds’ lifelong peace activities based on their correspondence from December 1984 until her death in February 1990 and taped interview with her. This book adds new information about Reynolds’ peace activities and life after returning to the U.S. Harada (1998) writes about Reynolds’ memoirs, and includes her essay, “The Phoenix and the Dove”.

- Ubuki (1999) reports that 54% of the books written by A-bomb survivors, and 79% of accounts about the A-bombings written in Japanese are not the publications by publishers.

- Ubuki (1999) notes that contrary to former expectations that the number of publications after the 50th anniversary would decrease sharply, the survivors keep on publishing their accounts even after 1995. The English-language publications of the books, originally written by Japanese, show a similar tendency.

- John Hersey's article, “The reporter at large Hiroshima”, was published in 1946 in the New Yorker, and created a sensation among readers around the world. Norman Cousins’ article, “Hiroshima: Four Years Later”, was published in the September 17th issue of Saturday Review of Literature in 1949. In the scientific field, the Manhattan Engineer District of the United States Army published a detailed report in 1946, The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Edith Sitwell, a British poet, is probably the first person who expressed the destruction by A-bombs in a literary work. She claims in The Canticle of the Rose: Selected Poems, 1920-1947 (1949) that an article about Hiroshima and Nagasaki in The Times on September 10, 1945, led her to conceive of the main idea of her poem titled “Three poems of the Atomic Bomb”.

- The authors of accounts in the third issue of Asa, a collection of accounts by mothers in Hiroshima, featuring “citizens’ life after the war” mention that their lives were even harsher after the war than during the war. A mothers’ study group in Hiroshima issued collections of their accounts entitled "Asa" (morning), for eighteen years. One of the members died of an A-bomb disease in 1963, which motivated their publication of a collection of memorial writings, the first issue of Asa, in 1964. The annual publication of a collection continued until the last issue of Asa, the seventeenth, was published in 1982.

- The author’s father is Takuo Matsumoto, the president of Hiroshima Jogakuin Girls’ School, who was the leader of the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Mission in 1964. The Matsumotos experienced the A-bombing 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter.

- Kusano (1995): 5.

- Fukagawa (1970): 64; Imahori (1960): 51.

- The Fukuryu Maru No.5, "the Lucky Dragon V," was a one hundred-ton tuna trawler that was dusted with fragments of the hydrogen bomb detonated by the United States 160 kilometers east of Bikini Atoll on March 1st, 1954. Lap, Ralph E. / The Voyage of the Lucky Dragon/ 1957. The English resource written by doctors is Health Effects of Atomic Radiation: Hiroshima-Nagasaki Seminar on Radiation Effects Research/ 1990.

- The Chugoku Shimbun, ed. (1966): 98.

- From February 1st, 1961, issue of the Chugoku Newspaper, Hiroshima’s major local daily. Senji Yamaguchi writes about his experience to join the delegates in his account, Burnt Yet Undaunted: Verbatim Account of Senji Yamagwchi/ 2002.

- Yamaguchi (2002): 161.

- Friends of the Hibakusha (1964) reports American citizens’ response to the first Peace Pilgrimage.

- Tomin Harada, in his memoir of Barbara Reynolds, (Harada 1998: 51) recollects that he heard her say “I too am hibakusha”, in the midst of a fast to protest against the extreme commercialization of Christmas, sitting on a bench in Peace Memorial Park in 1963.

- Yamaguchi (2002): 165

- Ubuki (1982): 202.

- Hiroshima-Nagasaki Publishing Committee (1978)

- ---. (1978)

- Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper, ed. (1966): 200. Omuta, Minoru/ “Okinawa no Hibakushatachi” (A bomb survivors in Okinawa) in Yamashiro (1965).

- Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper, ed. (1966): 266. Korean Hibakusha Survey Delegations were dispatched by Hiroshima Prefecture Department of the Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan), and appealed Koreans’ present conditions in Japan to the South Korean government and surveyed A-bomb survivors in South Korea.

- The Atomic Bomb Victims Relief Law, which provides some allowances to survivors, is only valid for those living in Japan. A-bomb victims in South Korea and South America have filed lawsuits demanding issuance of A-bomb Victims Health Handbooks. Aged victims in other countries request their registration as A-bomb victims in their countries (May 11, 2003, issue of the Chugoku Shimbun Newspaper)

- In this paper, the term, hibakusha, is used to mean those who experienced A-bomb blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For non Japanese, Linner (1995) explains the word, hibakusha, as follows: “the word is pronounced in three syllables: hi [as in “he”] baku [as in “back”] and sha [as in the “sha” of Iran] with the English translation, “explosion-affected persons”, referring to both to those who were killed by and those who survived the atomic bombings. Nasu (1998) explains that the term, hibakusha, refers both to the radiation victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as to those people who have been irradiated as a result of nuclear tests and accidents at nuclear power stations. The second syllable of the Japanese word which means A-bomb victims, baku, usually written with a Chinese character, 爆, which means “ to explode", has a homonym, 曝, which means “to be exposed”.

- Ubuki (1999) confirmed that the number of publication of accounts written in Japanese was larger in 1995 than that in any other year (5,496 publications of accounts in 1995 out of 37,793 total publications since 1946).

- 1999 Data Book of the World Vo1 2. Ninomiya Shoten

References:

The Chugoku Shimbunsha, ed. Nempyo Hiroshima (Chronology: Hiroshima). Hiroshima, The Chugoku Shimbunsha, 1995.

---, ed. Hibahu 50 shunen shashinshu: Hiroshima no kiroku (The pictorial report for 50 years in Hiroshima). The Chugoku Shimbunsha, 1995.

---, ed. Hiroshima no kiroku: Nempyo shiryo hen (The Record of Hiroshima: Chronology and Materials). Tokyo, Miraisha, 1966.

Ubuki, Satoru. Gembaku shuki keisai tosho/ zasshi soumokuroku (A bibliography of all Japanese books and magazines containing the testimonies by the atomic bombed survivors). Tokyo, Nichigai Associates, 1999.

---. "Nihon ni okeru gensuibaku kinshi undo no shuppatsu: 1954 nen no shomeiundo o chushin ni (The opening of the nationwide movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs in Japan: On the signature campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs in 1954)”, Hiroshima Heiwa Kagaku (Hiroshima Peace Science). Vol. 5 (1982): 199-223.

Hiroshima Interpreters for Peacc ed., Hiroshima Handbook, Hiroshima. Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace, 1995.

Kusano, Nobuo. Atomic Injuries. Tokyo, Tsukiji Shokan Company, 1995.

Fukagawa, Munetoshi. August 6, 1950: Chousen sensoka no Hiroshima (August 6, 1950: Hiroshima under the Korean War). Hiroshima, Gensuibaku Kinshi Hiroshima Kyogikai, 1970.

Imahori, Seiji. Gensuibaku jidai: Gendaishi no shogen (The age of A- and H-bombs: The witness of modern history), vol. 2. Tokyo, Sanichi shobo, 1960.

Yamashiro, Tomoe, ed. Kono sekai no katasumide (at the corner in the world). Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 1965.

Linner, Rachelle. City of Silence: Listening to Hiroshima. N.Y. Orbis Book, 1995.

Nasu, Masamoto. Hiroshima: A Tragedy Never to be Repeated. Tokyo. Fukuinkan Shoten, 1998.

Nakamura, Tomoko. "Eigoban Hiroshima Nagasaki bunken annai." Shin eigo kyoiku (The New English Classroom) (1983): 22 24.

---. "Annotated Bibliography" The Legacy of Hiroshima (1986): 141-150.

---. "A-bomb Literature: An Annotated Bibliography" in Hiroshima Handbook (1995):276-322.

---. "The Legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: A-bomb literature available in English", PRIME 12 (2000):83-95.

Hiroshima Nagasaki: A Pictorial Record of the Atomic Destruction. Tokyo, Hiroshima Nagasaki Publishing Committee, 1978.